For Nicholas Ray, dismantling the famous “American Dream” was almost a mission. Throughout his work, the American director explored, from multiple angles, the idealized yet unrealistic conception of that utopian society. In Bigger Than Life (1956), he launches a frontal attack on the model family and on a society that suffocates the male figure, reducing him to the role of breadwinner, forced into success regardless of the consequences.

On September 10, 1955, The New Yorker published an article titled “Ten Feet Tall,” which told the story of a schoolteacher in Long Island who developed an addiction to cortisone. From this article emerged Bigger Than Life. The screenplay developed by Nicholas Ray centers on Ed Avery (James Mason), a teacher who, to combat a serious illness, undergoes treatment with a so-called miracle drug and becomes addicted to it.

An ordinary man is transformed into the villain of the story, yet the director steers the narrative in a different direction. To avoid the strict censorship imposed by the Hays Code on Hollywood, Nicholas Ray constructs subtexts that antagonize the system, pharmaceutical companies, and unethical medical practices. Using the same strategy, he also confronts the pamphlet-like idea of suburban prosperity. Bigger Than Life portrays society as an oppressive entity that drives individuals toward self-destruction.

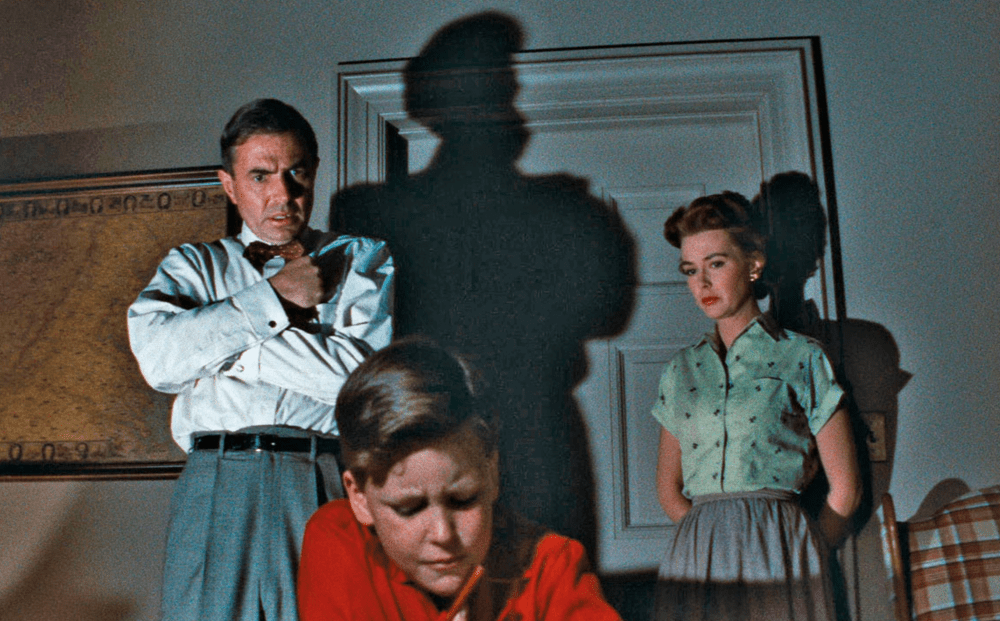

School, work, and home are the most common everyday spaces that are turned by the director into battlefields, both on an ideological level and in a physical sense. James Mason’s character becomes increasingly aggressive and, under the influence of cortisone, comes to believe himself bigger than life itself. The film’s narrative is built not only through dialogue but also through its remarkable cinematography.

The framing and compositions communicate what words cannot. The clearest example is the sequence in which the father locks his son in a room, forcing him to learn a school subject. The mother tries to intervene, but her efforts are futile. With the three figures sharing the frame, the director orchestrates a play of light and shadow in which the father’s shadow looms like a giant over the other two.

Bigger Than Life was poorly received upon its release, perhaps because of how directly it criticized society. Over time, however, this work by Nicholas Ray has gained recognition, especially for the way the director transforms a family drama into psychological horror. What is truly terrifying is not the addiction or Ed Avery’s transformation, but the way society systematically pushes individuals to that breaking point.